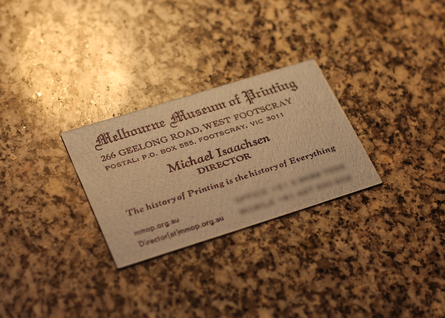

The Melbourne Museum of Printing liquidation auction was launched as both an online and an on-the-premises sale with a staggering 780 lots on offer in total. I had a strange sad feeling while perusing the online listings, and not just because of my personal connection with the museum. This monumental, miscellaneous compendium embodied one man’s single mindedness—and a vision that had spanned forty years. That man was Michael Isaachsen, the director and curator. Interspersed with printing and casting machines, tabletop presses and towers of type, were personal items from Michael’s past: an old telephone switchboard, picked up, no doubt, from his tenure with Telecom; his fridge, kettle and sandwich press; along with the chair he always held court from in the tearoom. The listings featured what I considered to be the significant print history collection, as well as items that had a more peripheral connection to printing—things like old typewriters, scanners and desktop PCs. Then there were those acquisitions that had a very tenuous or even an inexplicable connection to print history—boxes of magazines and newspapers, crates of phone books, gaming computers from the 80s. All this reminded me of the slogan I’d once assisted Michael in letterpressing onto his business cards: ‘The history of Printing is the history of Everything’.

You can experience a ‘feel’ of the museum in this excellent video created by Alex Reinders, Cameron Cooke and Alex Young in 2013.

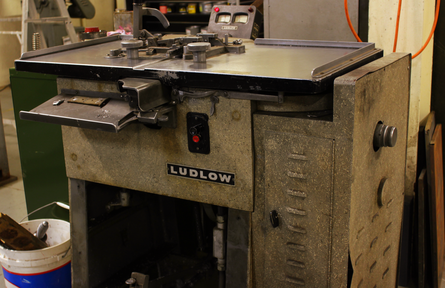

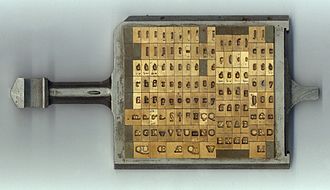

My partner, Kain and I placed our bids in moments snatched between duties at work, from our phones. The studio’s tools and equipment—furniture, chases, quoins and setting sticks—were bid for competitively; as were the antique type cabinets, the Vandercook press, on which I’d printed my first poster, and all the wood type. Michael had been particularly attached to his Ludlow casting machines. These could create display headings for relief printing by casting liquefied alloy into handset brass moulds (matrices). The museum featured a number of Ludlows and approximately 1,200 sets of matrices, all in their original cabinets. Another valuable part of the MMOP collection was the monotype casters and their accompanying matrix sets, numbering over 1,000—the most extensive collection in Australia, without a doubt. These machines and matrices can cast metal type in various sizes for letterpress printing. Their value lies in the fact that once the matrices for a particular typeface is gone, if there are no others in this size and face, it is lost forever. But more on this later…

Ludlow matrix cabinets (left) and a 'slug' cast from the Ludlow machine . Michael cast my pen name for me the day I first visited the museum.

Some of the wonders that formed a part of the MMOP collection. From left to right: wood type, two flatbed printing presses, a Typograph composing machine, a Linotype machine.

We had bid successfully; I was now the custodian of 23 cases of type and the very cabinet at which I’d typeset my first line. We’d also bought a small British tabletop platen, and a treadle press that is pretty rare in Australia—a circa 1890 Golding Pearl number 3. On the designated collection day, we hired a truck and made the drive down to West Footscray to pick up these treasures. When we arrived, the museum was in chaos. Vehicles were backed up in the narrow service road fronting the building. There were trailers packed with equipment and empty type cases, and skips so haphazardly piled with metal that I thought they were probably bound for the scrapyard. Pallet jacks and forklifts rolled in and out between the loading dock and the road, carrying presses and pallets and all manner of obscure, ancient machines. Here is an account of my feelings that day, from an email I wrote to a friend:

The truth is, even though it was horrible…there was also something wonderful about seeing those great machines brought out into the light, watching the wind buffet them and sweep away decades of dust. It was like watching a cavalcade of prehistoric creatures emerge from hibernation after thousands of years…From what I could see, all of these were trucked off to studios to be restored and used.

But…I will never forget the sound of Michael’s Ludlow matrices showering into a skip. The cases were being irreverently upended into it. I felt sick hearing that beautiful ringing brass and seeing the thousands upon thousands of intricate matrices—each a precisely-forged mother for an individual character—piling up in a sea of tarnished gold. Is this progress? I thought. I remembered the irreplaceable monotype matrices and wondered whether they would see the same fate. That was when I recognised a face among the busy crowd. It was Dan Tait-Jamieson, Secretary and Treasurer for The Printing Museum in New Zealand. I’d first met Dan back in 2016 on my trip to the Inaugural Meeting of the International Association of Printing Museums in South Korea.

Dan told me that his museum had bought all the monotype matrices—along with quite a bit of other equipment that would be shipped back to New Zealand. He said he'd called around all the museums and printers he knew in Australia to see whether anyone here would take the matrices, but without success. He explained all this in an apologetic tone, but I was relieved that the matrices had found a good place to be kept and used. 'We're open to passing them back to an Australian collection, if they want them,' he said.

This is just one positive outcome from The Melbourne Museum of Printing auction. I can report two others. Over many months following the auction, Kain and I toiled in masks, goggles and gloves to strip the Golding Pearl treadle press of its paint and rust and bring it back to its original condition. We were also able to buy replacement parts for it that had been lost or broken. When it was up and working, we christened the press Ethne and eventually used her to print my book covers.

The second happy story arose from a flatbed press—another that was purchased at the auction—by Keith, a friend of mine. Keith is well known for creating beautiful etching presses. This press had sat in the museum for decades. The rollers, made from composition (a mixture of glycerine and treacle), had melted in a gooey mess onto the bed and everything was covered in rust. On the auction’s collection day, Keith said it would come up well with a bit of work, but as I appraised the wreck being loaded into his van my head ached at the thought and I was doubtful that any part of it could be salvaged. But I had underestimated Keith’s skill—and his tenacity. The pictures speak for themselves. Eventually I bought this press from him and used it to complete my book’s preliminary pages.

These are just two stories with happy outcomes; I know that there are many more. For example, The University of Sydney’s Piscator Press purchased some of the museum’s equipment, which is currently being used for its artist residencies. It cannot be denied that there have been losses, and that it is unfortunate a collection of this scale has been dispersed. However, the treasures that were saved are now within the custodianship of people who understand their value—and who are in a position to maintain them or pass them on to those who can. As communication technology moves on to new frontiers, it will be even more important to preserve these gems of our heritage. Placed in smaller collections, universities and workshops, there is a high likelihood that they will be. We must remember that these tools and equipment were properly made. If they are restored and maintained, they will outlive us all.

Write a comment