When I started out on my bookmaking journey many aspects of the work that I hoped to create were unclear to me. I had no idea what typeface, binding structure, or paper I wanted to use. I was even unsure about the tales I would include. But I was set on one thing right from the beginning: my book must have marbled endpapers. Learning this art form so that I could realise my dream was one of the most delightful phases of my adventure, an experience that brought me back to that state of creative play that I had enjoyed in my childhood. To describe the art practice in the most basic terms, paper marbling involves creatively laying colours onto the surface of liquid and then transferring them from this surface onto paper.

In a former post I touched upon the challenges and successes that I encountered in applying this technique to my available materials. Yet there is more to marbling than just methods and mediums; like every book art, it is a gift that gives on many levels. Its creations are mesmerizing for their beauty and intricacy. It is a craft that, in learning and practice, might enrich and captivate one’s entire life. And, what’s more, paper marbling has a fascinating history.

Marbling may be seen broadly to have emerged in two forms: the Japanese and the Turko-Persianate. Although we don’t know exactly when and by whom it came into existence in Japan, examples of marbling can be found here from as early as the 12th century AD. This is known as suminagashi, translated to ‘ink floating’.

The Turko-Persianate form is known as ebrû (Turkish), and Abri (Persian), translated as ‘cloud art’. It emerged in these countries several hundred years after suminagashi, in the 15th century. While sharing the same basic method as Japanese marbling, ebrû differs in its tools, techniques, materials and results. Yet each form bears witness to fascinating cultural influences and possesses its own characteristic uniqueness and beauty.

Suminagashi, the Art of White Cloth and Water

In its traditional form, suminagashi required that sumi—or Chinese ink made from pine soot—be carefully touched with brushes onto the surface of a bath of pure water. The inks form lines of various thickness that swirl with the water’s constant flux and become elegantly flowing designs. The design is manipulated further by the artist with fanned or blown air, or by striking through the ink with a stylus, hair or string.

Each paper created in this way is unique and cannot be reproduced. The earliest motifs for the art were found in only two sources: the flowing motion of wind-blown white cloth; and in patterns that naturally emerge in slowly running streams. In its early years, suminagashi was used to embellish poetical works written in calligraphy onto decorative papers, and to beautify royal correspondence. For more than four hundred years it was produced exclusively by the Imperial Household and the country’s nobility, and prohibited to the general public.

The document above is the oldest known example of paper marbling, from Sanju-rokunin Kashu, a collection of poems by 36 master poets, transcribed for the Emperor Toba.

For the ensuing 260 years paper became such a valued commodity that feudal lords employed paper makers for their own supply, with some receiving payment from the people of their province in paper as well as rice.

Some of the suminagashi of this time, described in old records, was created with lines of fine gold dust on dyed paper called Torinko, which is made from the gampi plant. Gampi grows wild in the mountains and cannot be cultivated. Hōsho is another popular paper used, produced from the kozo plant. Hōsho is an appealing material for paper in Japan because it is easily cultivated and its fibre is long, strong and therefore durable.

Like all traditional art forms, suminagashi is more than a means of decoration; for some artists it was (and continues to be) a spiritual practice too. It is said to encompass the Buddhist philosophy of wabi-sabi, the acceptance of transience and imperfection. Because each suminagashi print captures a single moment in time, it is ephemeral—like life itself. Hence, it is a meditative aid to this mode of understanding.

Following the Second World War, the demand for fine papers and suminagashi dwindled. Although it is no longer as prevalent as it was in days gone by, in recent years artists from around the world have embraced this ancient technique and incorporated it into modern practices, recasting its significance within a contemporary context

You can watch one of my first attempts at suminagashi in the video below.

Ebrû, the Art of the Clouds

The form of marbling that finds its origins in Turkey and Persia differs from that of the Japanese, primarily in its materials. In place of pure water, ebrû artists use a gum-thickened size and employ paints for their colours rather than inks. In addition, more specialised tools are used for manipulating the colours dropped onto the surface into designs. These include implements bearing multiple styluses called ‘rakes’ and ‘combs’.

Marbling is known in Turkey as ‘cloud art’ for the likeness of the created patterns to the atmospheric wonders of the sky. Ebrû held an important position in Islamic art because of its use in decorating religious writings. Its spiritual significance in the Islamic tradition is described by contemporary ebrû artist Güliz Pamukoğlu in this way: ‘paper marbling is a spiritual activity akin to prayer. Art stems from spirituality. In ebrû, most of the time we're dealing with writings from the Qur’an. The very nature of calligraphy is to beautify these words by rendering them in ebrû.’ (1)

One of the best examples of religious writing embellished by ebrû is pictured here, in the Album of Calligraphies Including Poetry and Prophetic Traditions (Hadith) by Turkish calligrapher Shaikh Hamdullah ibn Mustafa Dede. This work was completed in around 1500 and featured ten pages of calligraphic samples surrounded by marbled patterns.

Ebrû emerged during the Golden Age of the Ottoman Empire and, like suminagashi, was quickly commandeered by the ruling powers. Originally this art form was used to embellish calligraphy, manuscripts, drawings and paintings, until the Ottomans decided to have their official state documents written on marbled paper, thus deterring forgery. This is one reason the technique was so jealously guarded, confined to a few court artists.

And yet, the secret couldn’t be kept forever. In the 16th century marbling made its way westward along the great trade routes to Europe, and its creations were readily used by the public to decorate—to line cupboards, cover boxes, and of course, bind books. New patterns were created by craftsmen bearing the names of their countries: French Curl, Old Dutch and Italian Hair Vein.

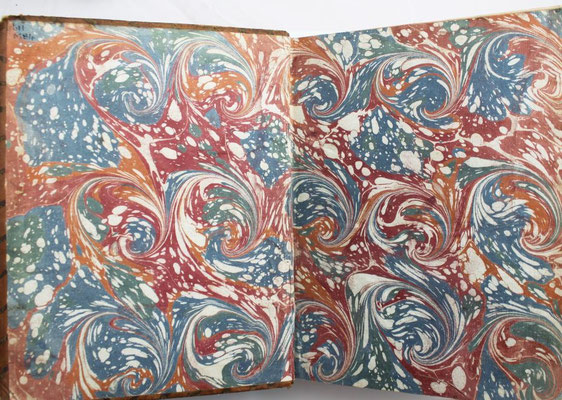

Some of the rare books in the special collection at The University of Adelaide

A turning point came in 18th century France when the French rationalist Denis Diderot enlisted artists and thinkers from throughout France to help write an encyclopedia, a summary of art and science as they knew it at the time. The 28 volumes of the Encyclopedie were published between 1751 and 1772 and included detailed descriptions of the art of marbling (pictured above).

Ebrû had found its way to the American colonies by the 18th century in the form of coverings for cheap books and almanacs. It is famously known that Benjamin Franklin commissioned his $20 bill, issued in 1776, to be marbled on one of its short ends to prevent forgery.

In the United Kingdom paper marbling was a thriving industry because of its fashion in book endpaper decoration. However, it was kept a close secret by craftspeople until the 19th century. The apprenticeship system allowed masters of marbling houses to employ boys from the local workhouse in exchange for bed and board and the promise to teach them the trade—a promise that was never delivered. The boy was taught only one step in the process, such as how to prepare the paints, or how to make the bath. Work areas were screened off so that no one could learn from anyone else. After completing his apprenticeship, each boy was turned out into the street, and in this way the master protected the secret of his craft. Then, in 1853 a self-taught marbler named Charles Woolnough—and a man who had taken exception to this malpractice—published The Whole Art of Marbling, a textbook that described every stage of the process.

At the end of the 19th century book production became mechanised and marbled book covers and endpapers went out of fashion. Yet in the late 1970s there was a revival in marbling with the crafts movement. In recent decades marbled endpapers have become fashionable again. Today bookbinders and craftspeople alike are taking an increasing interest in the paper and its relevance in a variety of modern applications.

Watch a mini documentary on how I created the endpapers for my book in the video below.

(1) Quoted text from Society of Marbling 2006 Annual,

https://whatapageturner.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/03/annual_2006.pdf p.43

Write a comment