In emails from 2016 to a friend, I described my first visit to the Melbourne Museum of Printing. For me now they are a cringing reminder of the naivete and optimism that accompanied my first ventures into my book project:

'The museum's in what looks like a newish, abandoned warehouse. Newish, because it's a modern, glass-fronted steel-constructed monstrosity; abandoned, because the frontage is faded and covered in dust, with the only thing to designate it being a moisture-buckled piece of paper tacked to the inside, printed: Melbourne Museum of Printing. That kind of sums up the vibe of the place, really; it's not abandoned, but it has an air of abandonment, what with the old, obsolete machines populating the place, and the quiet, big space.

Michael, the director, puts me in mind of the abbot of some dying monkish order. He's cheerful, full of knowledge and enthusiasm, but...resigned. For the three ensuing hours he led us…through the history and process of printing, as lovingly as that old abbot describing the customs of his order. It wasn't boring, by any means; it was boggling. There's so much there to take in and so much to learn! The place is big enough, and has enough equipment, to run an around-the-clock newspaper, but there were only a handful of volunteers skulking in the corners as though expecting to be evicted at any moment. And I think their situation might be as bad as that.'

The museum’s collection, amassed over almost a lifetime by Michael himself, was stored on a rented industrial property that was, by this time, hundreds of thousands of dollars in arrears. The business had been unable to bring in the income, through visits and workshops, that would even come close to covering the rent. Michael spoke openly about this to anyone who visited, hoping to gain financial support for what was undoubtedly a collection of historical significance. At the time this gave me further motivation to print my book there:

'My sense is that the place is an amazing treasure trove waiting to be cracked open and polished into life. When I mentioned my thoughts on having a book printed Michael's eyes lit up. He showed me the machine it could be done on, the type we could use; he did his calculations to determine the number of pages, and estimated that it would take "up to two weeks of solid work"…Going by his ballpark estimation, the project…would cost about $2,000. That's not including materials. But I know right now, without looking into it, that it's way cheaper than having someone else do the project—and I'd come away with all the skills.'

I’ve often reflected over the years on whether—had I known that ‘up to two weeks’ would turn into sixteen months of weekends, and ‘$2,000’ would blow out to the cost of a university degree—I would’ve continued on this course. I’ve had to delegate that one to the place where all the other unanswerable questions go!

I started out on a monstrous proofing press, used in its heyday for printing some of Melbourne’s city maps. Having proven itself through decades of industrial use, I felt confident that this machine would be up to the relatively small task of turning out a couple of hundred copies of my book. Michael guided me through the fundamentals of setting up to print. I learnt how to lock my carefully-set type onto the press and apply ink to the system of rollers. We worked through the basic elements of adjusting the print impression with the use of ‘make-ready’. This involves building up with paper the areas on the press where the sheets will make contact with the type matter, so that the words and images print evenly. And I learnt about ‘registration’—making sure the print is aligned properly on the page. Having covered these things, I felt confident and eager to start.

But, there was a problem—or, should I say, there was one problem after another. It might be that each time I pulled a print the type rippled on the press like pin art, slurring the page. Or, when I applied ink, it was either too little or too much. Or, my so-called system of ‘make-ready’ turned out an even impression the first time, but was too heavy or too light after that. Or, I’d fix the inking problem only to find there was another type problem, impression problem, or an intermittent problem that seemed to have no source. Press problems, I’ve found, arise from a nightmare of variables (or gremlins) working together to wreak havoc on the amateur’s mind.

As I encountered these troubles, Michael faithfully stayed on through many tedious, frustrating hours, helping me to deal with one issue at a time. He cared deeply about my project and about my succeeding in it, but in the end, these problems were beyond even his knowledge. Michael’s area of expertise lay in casting type—not in the specific techniques involved in turning out a book to the quality that I needed it. I was later to learn through hard-won experience where I’d gone wrong in each case. My attempts at make-ready were as haphazard as a kindergartener’s approach to scrap booking. I wasn’t setting my lines of type as tightly as I should. Or, I was locking the type matter up too tightly in the chase. Added to this were the issues created by using a press with a distribution roller that wouldn’t oscillate properly and that hadn’t seen a service in my lifetime.

To make matters worse, my working hours were less than ideal. Michael’s schedule didn’t allow him to open the workshop for me before 2 pm, so I was driving 125 km, then labouring through the night—often until 3 or 4am. Nevertheless, I forged on. Some problems I resolved through hours of trial and error; others, I mitigated. The latter approach involved a band-aid solution that necessitated a whole lot of extra work—things like levelling out the type with a plane every ten minutes, or wiping the ink off an area that was printing too heavily before running each sheet through the press. These measures—troubleshooting, mitigating, testing, printing—constituted an agonising labour that pushed me to the edge of my sanity, and sometimes tipped me over the edge. I’d spend four hours getting set up to print, start to run the ‘good’ paper through, then face a new problem and have to begin setting up all over again. If I had my fortitude on the day, I’d go off and cry in the toilet, then return to it with resignation; if I didn’t, I’d spin into a frustration and panic-induced frenzy and print anyway. I wasted so many sheets of expensive paper in my ‘frenzies’ that I had to go back to my supplier and sheepishly ask to buy more.

From an email to a friend during this period:

'…it's been ludicrously slow. And it's very hard work. I was over the press for fifteen hours…Today I'm dog tired. But it is getting faster and…there is progress. If there were no progress I'd be in despair by now and would've given up.'

From the Sublime to the Ridiculous

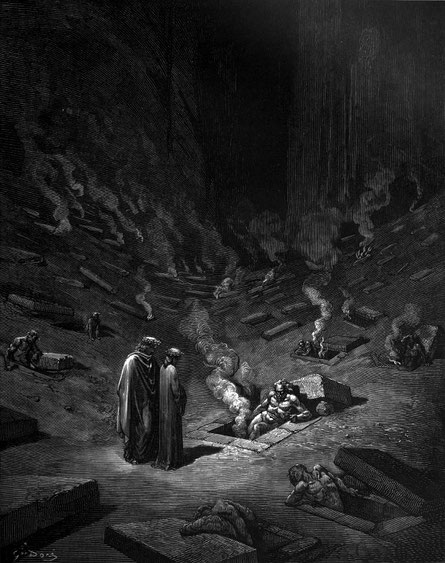

There is so much truth to Thomas Paine’s assertion that ‘The sublime and the ridiculous are often so nearly related that it is difficult to class them separately.’ While, at the time, this three-and-a-half-month period was like navigating my way through Dante’s Inferno, I now see it as one of the most valuable times in my life. Every session tested my endurance. While labouring in the early hours over the press, I’d enter a kind of delirium where my body didn’t feel like my own and I’d glimpse dark figures standing in recesses of the warehouse. Maybe my bungling efforts had roused the exasperated ghosts of printers past! And when I’d finished my run and stepped from the museum’s underworld out into the night, the city lights transformed Melbourne into a fairy realm. The breeze, sweeping in from Port Phillip, had never felt so good on my face. From there, I’d drive a short way—to the home of one of two gracious friends who had allowed me to stay. I recall arriving at my West Footscray friend’s home at four one morning, plugging my air pump into the cigarette lighter, and inflating my mattress on the roof of my car. I was wrecked with fatigue—but I’d never felt so alive. I giggled at the absurdity of the situation, then dragged my bed up the two flights of stairs to his unit.

Experienced letterpress printers will be staggered to know that I spent close to 200 hours printing 160 copies of pages one through to twelve. They will say that I should’ve gone elsewhere and sought better equipment and guidance. They are probably right. But at the time, I’d overcome so many obstacles to get where I was that the thought of facing more in setting up again was too much for me. I was also kept at the museum by a sense of loyalty to Michael and his dream of its continuation—a dream that I shared. But midway through August of 2017 I knew I couldn’t continue on this course. I was happy with the pages I’d turned out, but I was living every day in a grey haze. I was exhausted.

From another email:

'I've decided I'm going to ring him [Michael] this week and explain that the travel and protracted hours have been too much for me. I'm going to ask whether, if I were to find another press, he would be willing to loan me the equipment I need…I've got a couple of inquires I could make (HipCat Printery in Kyneton is one). So, watch this space...'

Michael was kind enough to loan me the equipment I needed to continue printing elsewhere. I will always be grateful to him for offering all that he could: his enthusiasm, practical support and advice; and, above all, for never doubting that my harebrained idea was possible.

Write a comment

Philip Boug (Sunday, 29 August 2021 23:41)

You are an amazing girl Beck, and will never know how much I admire your tenacity and drive.

Yes, we can all look back with 20/20 hindsight and say, "I should have done it differently", but then we would not have had the growth experience that we needed to become who we are now. I dabbled with letterpress for a short while while working at a shop that ran both platens and offset machines. A friendly letterpress guy showed me the basics of operating his precious Heidelberg Platen and then introduced me to the mysteries of makeready. It was hilarious, and I was hopeless, but after a few hours of free-timing after work I produced a passable page. Note, ONE passable page, not multiple pages as per your project, this was one quarto sheet! He gave willingly of his after-hours free time, because I think that he wanted to highlight to me how "easy" offset printing is compared to letterpress, and he was mostly right... it is! But of course offset has it's own tricks and quirks. The platen was in my opinion a dangerous machine to operate by a novice, and very easy to severely damage too. I don't think he would have left me alone for too long.

Would the tradesmen of today spend many unpaid hours with a young guy like me, purely because he could see that I was genuinely interested? I would hope so...

Best wishes for now,

Love, Phil

Beck Sutton (Tuesday, 31 August 2021 03:03)

Thanks for your kind words, Phil, and for sharing your letterpress story. I've encountered so many people who've either been a part of the letterpress trade or have had a little experience with it, as you have, and in every single case they have great memories to share. The print room is a hothouse for stories.

I don't think I'd go near the Heidelberg Platen--too dangerous! I even find my little Golding Pearl a challenge, trying to keep my fingers safe.